Winning the de novo portion of the Adaptyv Nipah binder competition

The Adaptyv Nipah binder competition recently released results. If you're not familiar with it, the objective was to design protein binders to the Nipah virus G protein. Designs were tested in the wetlab and ranked solely based on binding affinity. My last post describes our own entry in the competition, which won the in silico round. I did not expect to also win the in vitro round! To quote myself:

If they do bind strongly, I'll have to substantially revise my understanding of what is necessary for successful computational binder design.

Well, they did bind strongly: we got first place among the de novo designs. Actually, we also got second, third, and fourth places. In fact, a full 9 out of 10 of our designs bound for an astounding 90% success rate. This is far better than any other team [[1]], and far better than I expected -- these designs were an experiment in removing filtering and ranking from the standard design pipeline.

So, should we completely rip out filtering and ranking code in binder design pipelines? Even ignoring that this is a single experiment against a single target, I think this is premature. First, I'd like to consider some possible explanations for why we won -- and whether or not they might generalize to other targets. This post discusses a couple of theories for why this happened and what this means for computational binder design going forward.

It's clear that inverse folding, filtering, and consensus ranking with another model were not necessary. This in itself is a useful finding, though it's not clear it'll generalize to other targets. It's quite possible this is due to our unique sequence recovery loss term, which is gratifying. As an aside, we found that none of these binders would have passed BindCraft's default filters (even when using AF2 initial guess), though many of them almost do. Most designs failed the unsaturated hydrogen bond filter, which has a stringent, static cutoff that should probably scale with interface size.

I think there are two likely explanations for why we won, but they both come down to roughly the same thing: I didn't manually specify an epitope. Instead, I let the optimizer figure it out for itself, and it made a better choice than I would have [[2]].

Actually, it made a better choice than I did! For one of my designs I imagined myself to be a tasteful structural biologist, and manually cropped the structure and modeled in some glycans. This was by far my worst binding design. At the risk of overinterpreting a single data point, I think there is a valuable lesson here: sometimes it's better to use these models in a declarative, rather than imperative fashion. That is, it's better to ask for what you want (a binder), rather than how to get it (a binder binding to this specific epitope). To be clear, in many circumstances what you want is a binder to a specific (functional) epitope, but that wasn't the case here.

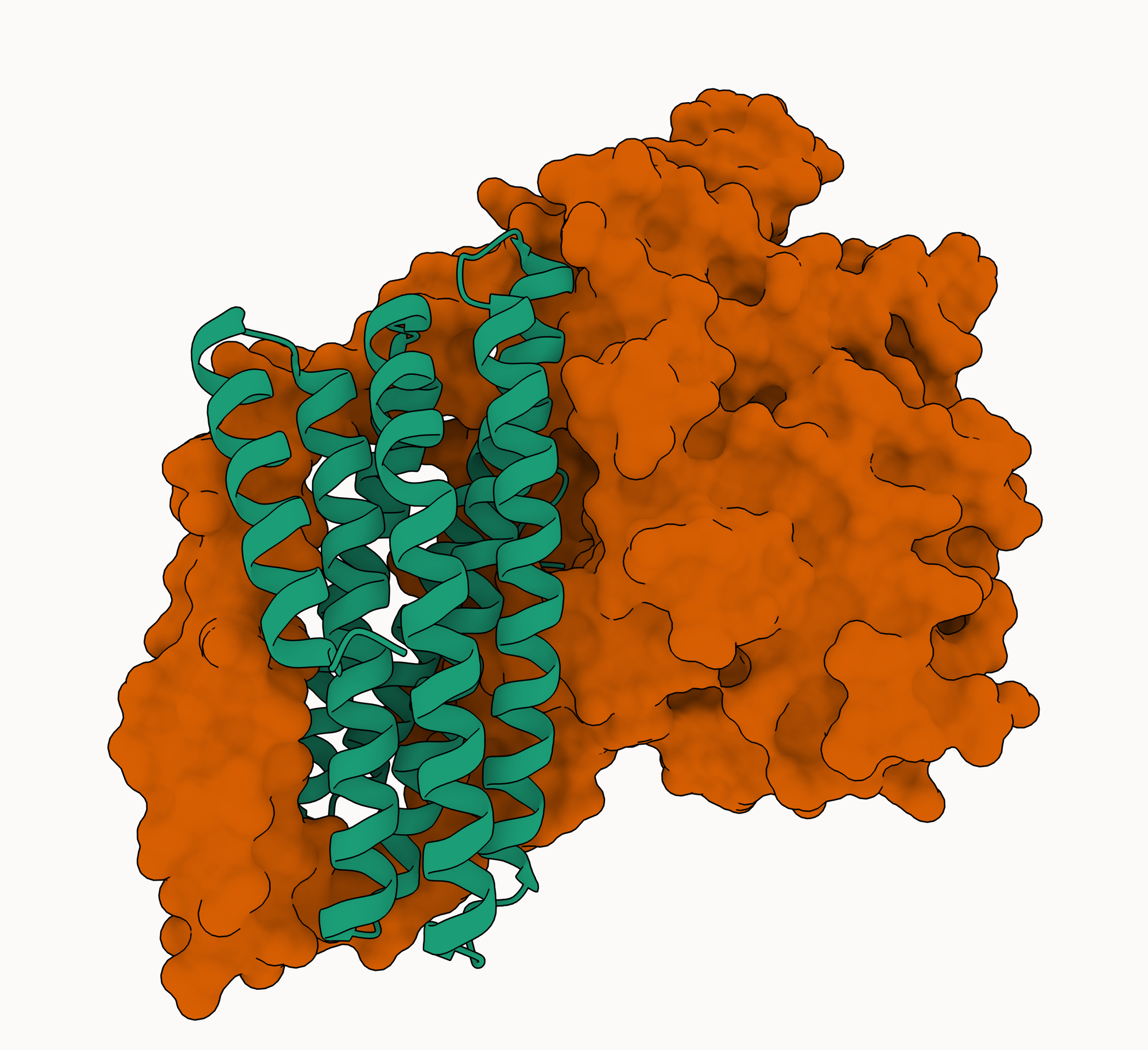

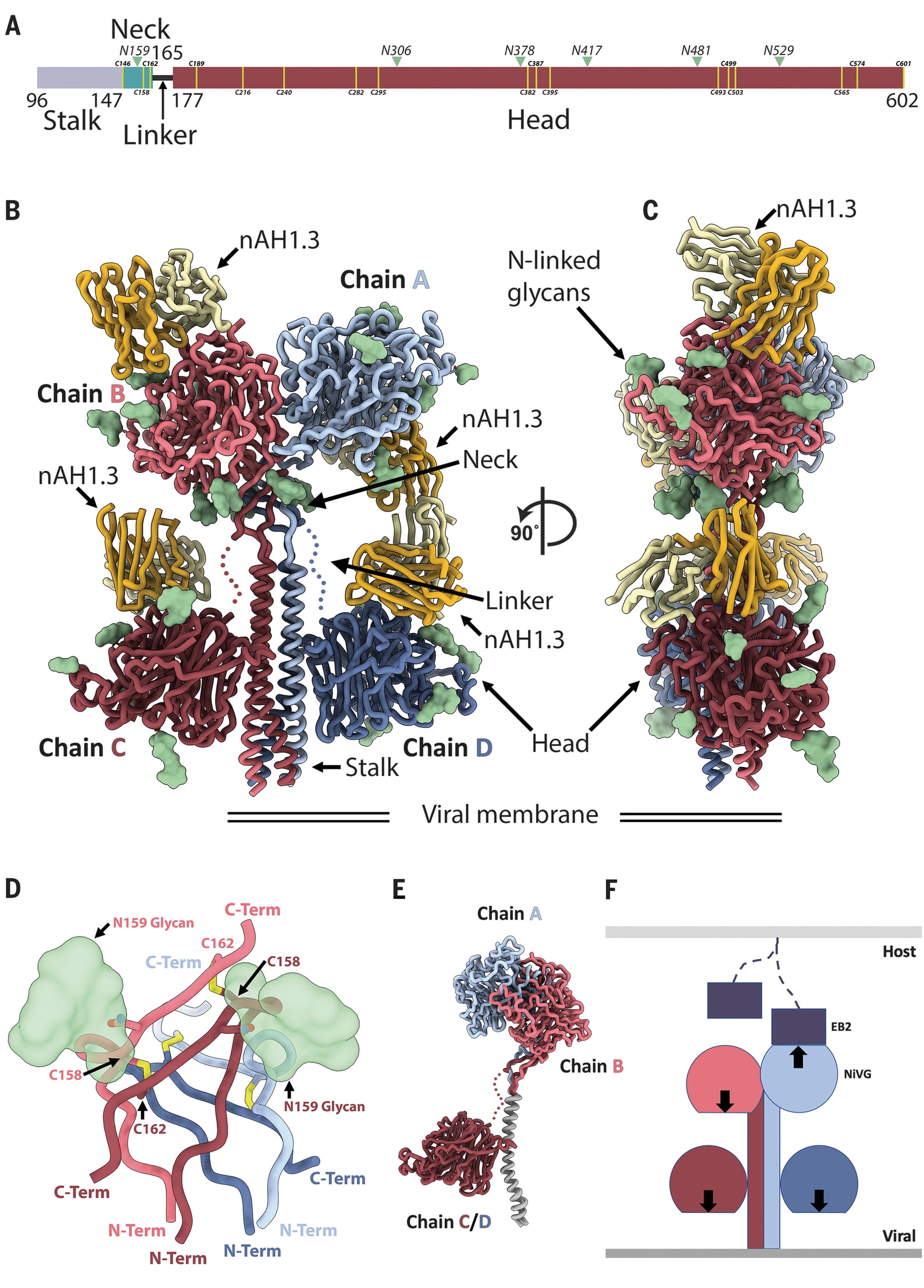

To understand why these designs worked so well, we need to take a short structural biology detour. Here I'll closely follow the (rather excellent) paper, "Architecture and antigenicity of the Nipah virus attachment glycoprotein". I highly recommend reading it in its entirety if you have time.

In solution, the Nipah G protein exists as a tetramer (a complex made up of four identical protein chains). Each of these chains is composed of a head domain (which binds to the host cell receptor ephrin-B2) and a stalk domain (which connects the head to the viral membrane). The head domain is a complicated (to my untrained eye) beta-propeller structure, while the stalk domain is a single extended alpha helix.

The four copies of the G protein are bound together mainly (though not exclusively [[3]]) through interactions in the stalk: all four helices roughly line up next to each other (in different orientations) in an arrangement called a coiled-coil [[4]]. Coiled-coils are commonly used as oligomerization domains: regions by which homo-oligomers (complexes with multiple copies of the same chain) are assembled. Of note for our purposes is that they are very easy to bind with large, extended helical interfaces: they are very common (in PDB), the interfaces in PDB can be very strong, and they're often quite stereotypical.

Theory 1: our designs bind the oligomerization tag in the stalk

How does this relate to our designs? Well, we presented a single copy of the G protein ectodomain with an unbound "bind here" tag and asked our model to complete the picture. Unsurprisingly, our designs bind the stalk. It turns out this was a very good choice relative to the ephrin-B2 binding site on the head domain, which is fairly small, recessed, near occluding glycans, and mostly loop-mediated [[5]]. This is the first theory explaining our results: we were the only team that tried to engage the stalk with a relatively large binder capable of recreating something like the native helix-helix interface.

Theory 2: our designs bind both the stalk and the head

The second theory is closer to my original intention: by not specifying a binding epitope and using large binders, we were able to engage multiple epitopes on the target simultaneously, increasing overall binding affinity through avidity effects. In fact, if you look at the Boltz-2 PAE plots, our designs appear to bind both the stalk and the head, and as much of the rest of the target as possible. Avidity effects would be quite strong with a tetrameric target like this, even very moderate affinity for each epitope could add up to very strong overall binding. The fact that bivalent kinetics curves fit the BLI data for our designs does weakly support this theory; though of course even a single epitope binder could show bivalent binding to a tetrameric target. Other models disagree with Boltz-2, though, and typically show binding only to the stalk.

A remaining open question (for me): if the interactions in the stalk are so strong, how do our designs bind at all? We'd expect to see a very slow on rate if it's unlikely our binders displace the other chains. I suspect the answer is somewhat complicated and involves avidity + disulfide bonds in the neck.

Conclusions

In general, I'm not ready to go completely hands free for all targets; at least until models and pipelines get better. For most applications you want to target a specific functional site anyway. But even for applications like this competition where you don't care about the epitope, it's probably still not a good idea to completely forgo epitope targeting: success rate varies wildly across epitopes, and letting the model choose a single, bad epitope is a real risk [[6]].

It's fair to conclude that turning off all filters is not as bad of an idea as it sounds. I'll probably skip inverse folding in favor of our sequence recovery loss more often. I'll definitely keep ranking with multiple diffusion samples when I use AF3-style models. Finally, I'm very curious about the generalizability of these alpha solenoid-like designs to other targets.

The main takeaways for me are really:

- there are a huge number of hyperparameters for these design models/pipelines, large areas of the space still remain unexplored and we need more data.

- we should trust these models a bit more.

Thanks again to the entire team at Adaptyv for running this competition. It was a lot of fun, and we most likely wouldn't have tried such wild designs without free testing! If you've got alternative theories for why these designs performed so well, or feedback, reach out.

Footnotes

[[1]]: Notable exceptions to this are a pre-release version of BindCraft2 and Latent-X both of which had a ~30% hitrate.

[[2]]: In general I'm skeptical of statements like this. In fact, I might be actively hostile to them: we wrote mosaic to give as much control to the user as possible. Unfortunately, in this case I think it's probably true. A less hyperbolic way of saying this is (almost) everyone chose to bind to the head domain, while we (or rather, the model) chose to bind to the stalk (and maybe also the head). The stalk domain is probably an easier target.

[[3]]: I'm going to ignore disulfide bonds in this discussion for simplicity's sake. Suffice it to say there might be some.

[[4]]: Some might just call this a four-helix bundle.

[[5]]: Of course most people chose this epitope because it's the functional binding site, and thus more likely to be neutralizing. It also has many binding partners in PDB. We didn't try to make neutralizing binders, but I can't help but say something about this.

Adaptyv notes that their neutralization assay is actually a binding competition assay with ephrin-B2, but it's known that there are neutralizing antibodies which bind to the stalk, if you go by this paper (though they're far less common than those binding to the head). This means it's possible our designs actually are neutralizing. Even if they were, though, I certainly wouldn't want to take these things as drugs for many other reasons.

[[6]]: There are of course choices other than manual selection: non-IID sampling, running an epitope prediction model first, etc. Florian Wünnemann actually did target the stalk after running an epitope prediction model, PeSTo.