Petri: abstractions for lab automation

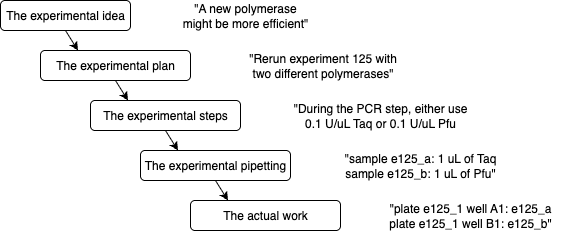

Molecular biology thrives on abstractions: even the simplest experiment starts with an idea and is progressively made more concrete.

As a software engineer, abstractions are familiar. Developers typically write code in a high-level programming language that gets compiled into an intermediate representation, then assembly, then translated to microcode, and finally executed.

So you can imagine my shock when I learned that liquid handling software for molecular biology barely abstracts anything at all.

This is how you tell a liquid handler to move 100 µL from one well to another:

left_pipette.pick_up_tip()

left_pipette.aspirate(100 /* ul */, plate.wells["A1"])

left_pipette.dispense(100 /* ul */, plate.wells["B2"])

left_pipette.drop_tip()Okay, it's better than gcode, but this is not a meaningful abstraction.

This is how you tell the automation system we designed, Petri, to do a multi-sample PCR:

The differences in approaches matter. We’re a small team trying to expand our wet lab capabilities with automation. When you can only interact with a liquid handler by writing imperative code (or worse, writing imperative code using a visual editor), then:

- Change is hard: I’ve heard anecdotes that reconfiguring a workflow from 96-well to 384-well plates can take two months of work.

- Productivity stalls: Scientists aren't going to use it. Without automation, lab work stops when people aren’t in the lab. Nights and weekends become dead time only for incubations.

- Knowledge gaps form: Handoffs to automation specialists mean rebuilding workflows from scratch, often missing critical context from experimentalists that only surfaces through rounds of debugging.

- Consistency is challenging: Changing values in one step can lead to cascading effects that are difficult to manage when values are manually specified. This is not just for volumes but also for enzymes, correct thermocycle routines, library prep type, and more.

- Documentation drifts: There is no standard wetlab ELN style. This makes replication hard and communication within a team difficult. With the rise of AI, making processes legible will only become more important. Workflow definitions are an opportunity to encode what people are doing - not just robots.

Our automation vision

Petri is an attempt at making software that addresses these challenges. There are a few guiding principles:

- Optimize for ease-of-use and prototyping: Existing systems already prioritize experts maximizing workflow throughput but ultimately limiting adoption.

- Enabling researchers to try an idea on a liquid handler could increase their productivity, and with multiple liquid handlers multiple ideas can be tested in parallel freeing up even more time. This way you can scale research without having to scale teams.

- Split the what from the how: Ask users what they want to do and have software handle exactly how it should be done.

- Inputs, outputs, and protocols define the experiment; labware, well assignments, whether the moving arms are robotic or human, and many other details are swappable. Current systems overburden researchers by requiring them to specify details beyond what is required for manual pipetting. Handing the how over to Petri enables scientists to start leveraging automation without becoming experts.

- Workflows should be specified declaratively, not imperatively. The amount of sample you need at any step is determined by how much material the whole workflow needs to output at the end.

- Volumes can be automatically calculated in reverse. Users tracking them manually is error-prone.

- Enable workflow abstraction: Once a workflow is validated, it should be available for use as a callable block in future workflows.

- A simple experiment might require a golden gate reaction, followed by a PCR, followed by an NGS prep. Users should only have to create a workflow once to use multiple times. Connecting validated blocks into a workflow makes it trivial to prototype long running protocols composed of many steps.

- Incorrect specifications should be obvious. If, for instance, the user forgets to include a material in their reaction, it should be trivial to see that it is unused.

- Petri’s encoding should support all steps for any experiment. A workflow isn't just pipetting. It’s an entire process from start to finish that can be composed using human wet lab steps, robot wet lab steps, and digital pipelines. This total encoding helps with knowledge sharing and documentation.

- We haven't implemented this yet but Petri's UX is built for it.

Why we're open sourcing Petri

As a small company building at the intersection of wet-lab biology and AI, we leverage many open source technologies. If an open source scheduler that met our goals existed, we’d be using it. We’re open-sourcing Petri in the spirit of making the change we want to see. Even if, in the long run, Petri stands as only a futuristic demo and a glimpse at what’s possible, someone else taking these ideas and designing something much better would be a success. This type of infrastructure is a rising tide that lifts all boats.

In the rest of this post we'll dive deeper into how Petri works.

- A brief tour of Petri

- AI doesn't obsolete Petri - it enhances it

- Values flow down, volumes flow up

- Critiques of Petri

- What's next for Petri

A brief tour of Petri

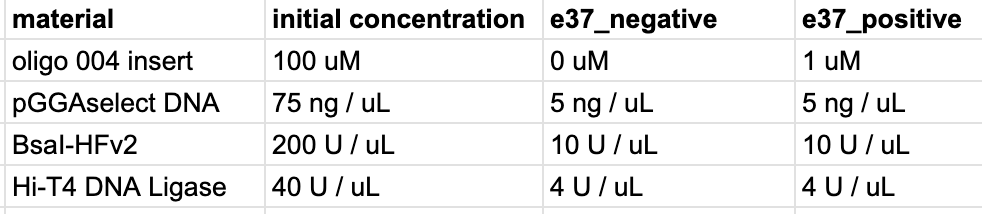

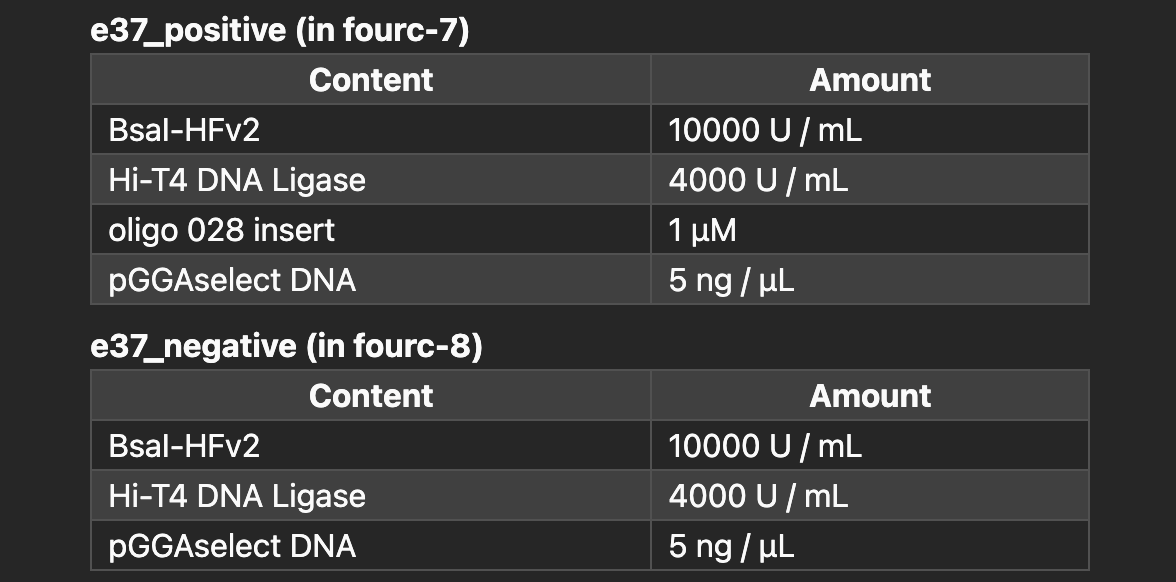

Consider the example of a pipetting workflow. When planning an experiment traditionally, researchers might prepare the following table:

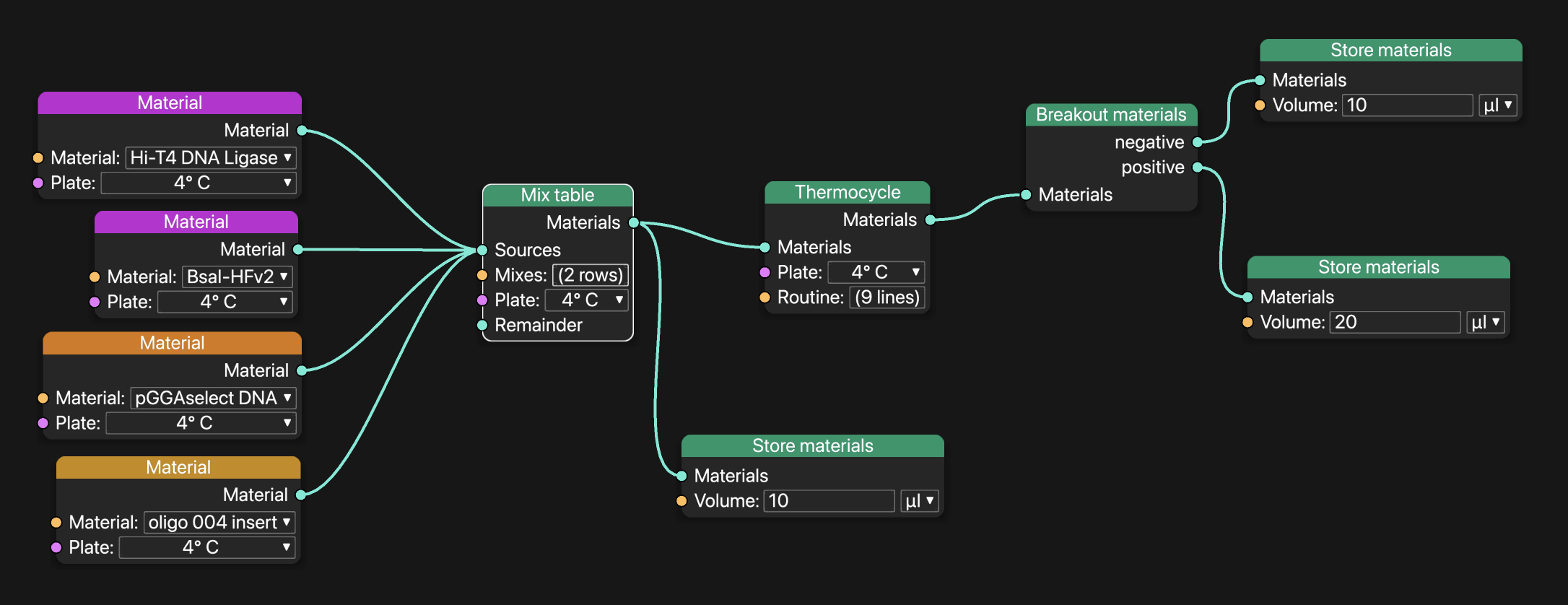

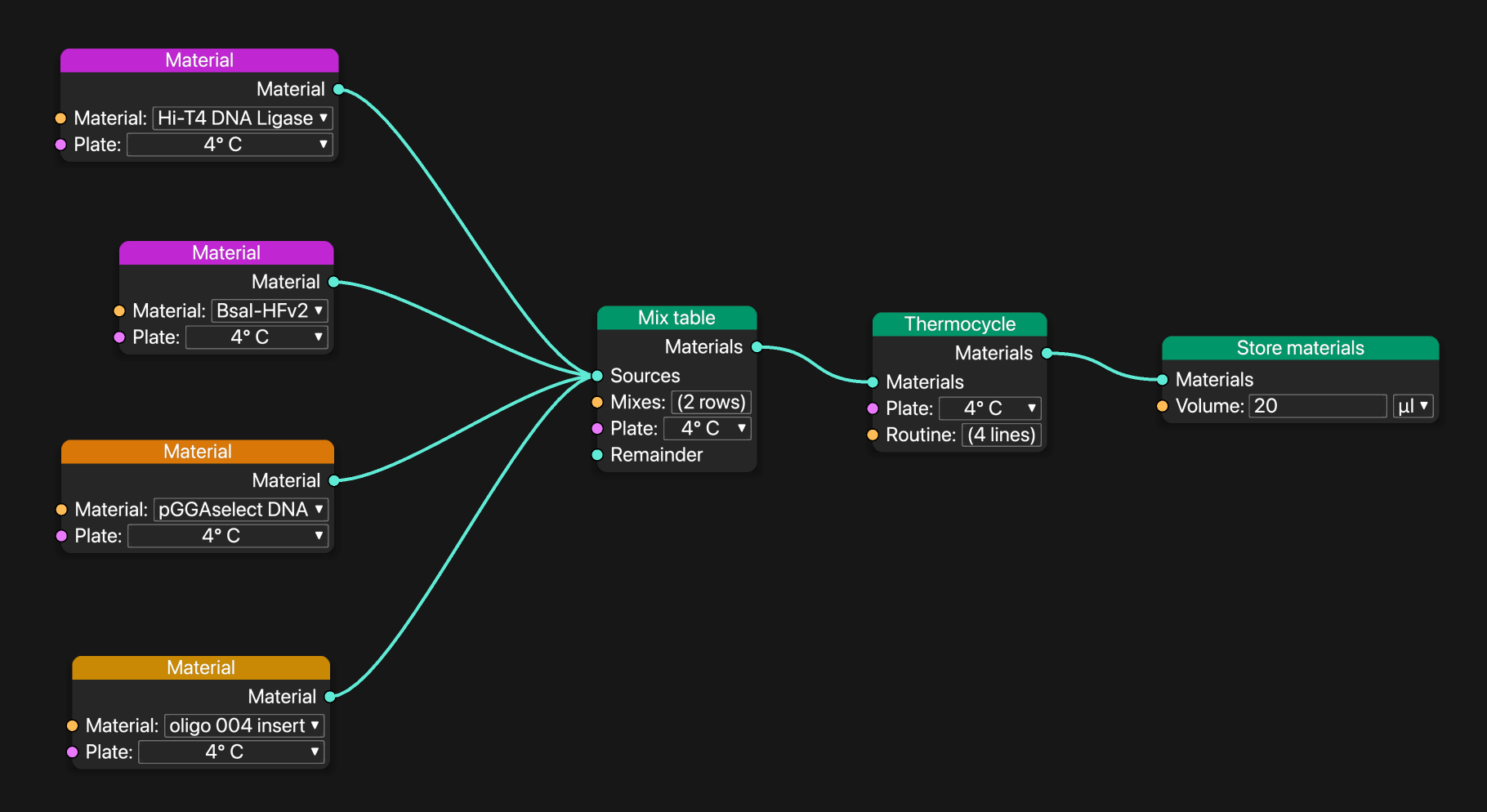

Here is how that reaction would be built in Petri:

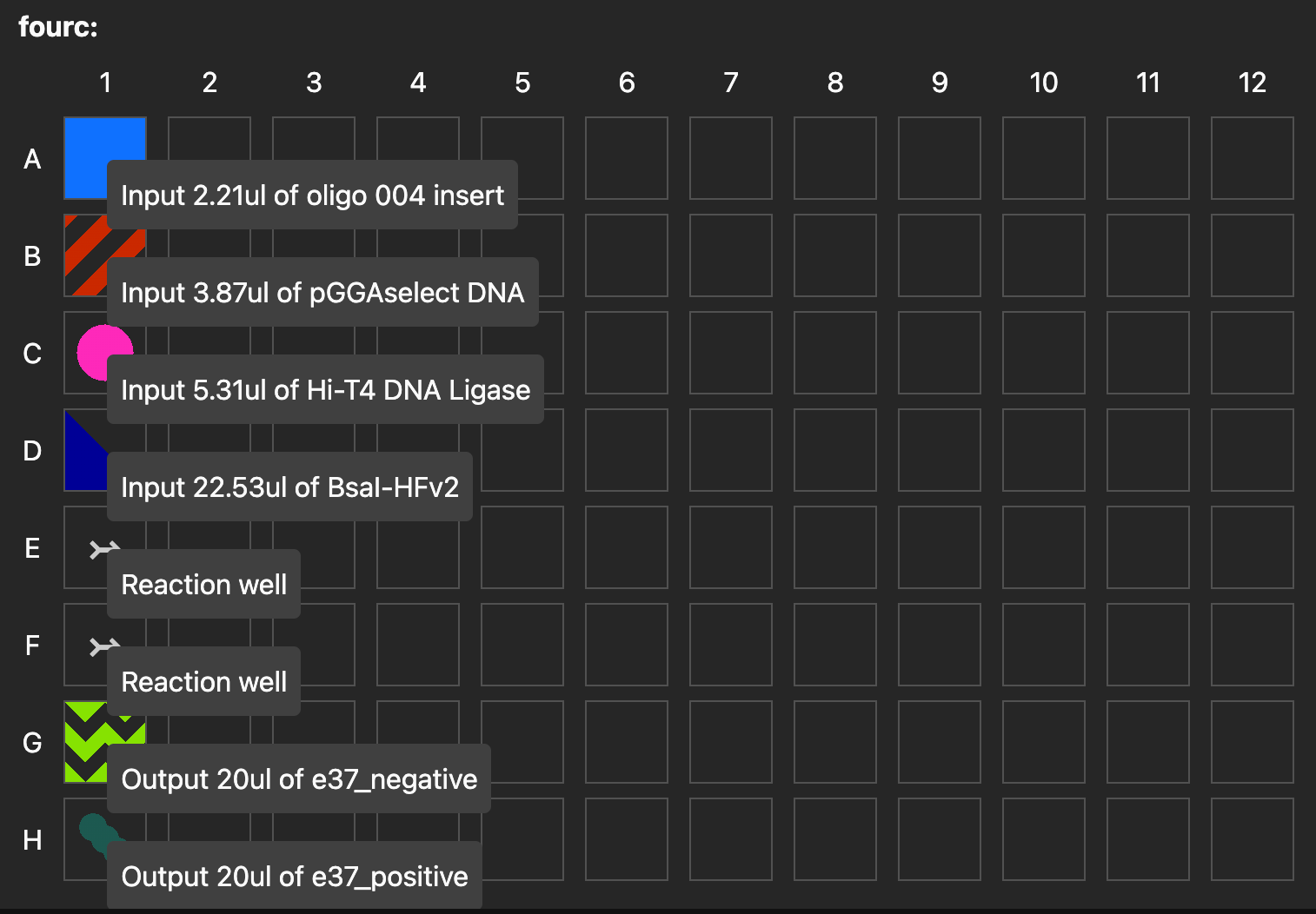

A Petri workflow that mixes four materials and produces two samples with 20 µL. To improve liquid handling robustness, Petri automatically adds 1 µl of dead volume to every well.

The first thing to notice is that Petri doesn't ask the user to assign wells. Petri automatically calculated which wells to use as inputs, which to use as dilution wells, and which to use as outputs. In this case it doesn't make sense to use a premix, but Petri automatically makes premixes where appropriate.

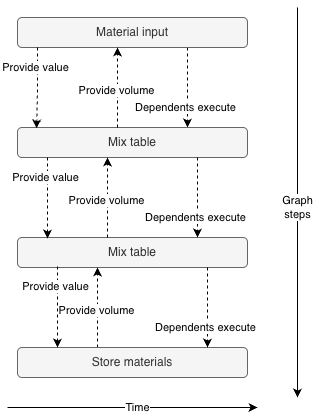

Second, values flow down the graph and volumes flow up. In the following graph, the amount of material to make when mixing is determined by the block after thermocycling. Petri passes the required volume from the "Store materials" block to the thermocycling block, and then up to the "Mix table" block. At every step along the way, Petri adds dead volumes to the wells according to its configuration.

This golden gate workflow is specific to "oligo 004 insert", but it’s trivial to turn this into a reusable subgraph.

There are many ways to help the user catch errors. One example: Petri tracks the concentrations of materials in samples through every step. This makes it easy to verify that the output of mix reactions, or of thermocycling routines, has all of the inputs you're expecting.

Because Petri knows all of the inputs and all of the outputs and handles scheduling, it tracks liquid levels and can calculate pipette head Z-offsets appropriate for the labware (caveat: this release doesn't include these calibrations).

Finally, our internal version of Petri has an extension to make it easy to launch workflows on our Opentrons Flex and walks experimentalists through setting up the deck.

Petri prompts the user to load the deck and store the materials when the workflow finishes. This video used a simulated robot so all pipetting and thermocycling steps completed instantly.

AI doesn't obsolete Petri - it enhances it

Everyone has considered teaching LLMs to write low level liquid handling code. Large companies, small companies, and even talented individual hackers are trying it. So it's fair to ask: if LLMs can just write some code, why do you need Petri?

First, I don't believe LLMs writing low-level code will unlock liquid handlers for general use. LLMs write software successfully when the action → validation loop is very fast. They write some code, they run it, they see what it did, and they adjust. This falls apart for liquid handling code. Validation takes hours, and the output is often a binary success or failure with little information on intermediate steps. In this environment, failed liquid transfers will be expensive and hard for them to root-cause.

There are steps you can take to help: for example you can make a material tracking system and allow the LLM to investigate samples at every step in simulation. But now you're no longer writing low-level code.

Second, LLMs benefit from abstractions just like we do. We don't ask LLMs to write complicated software in assembly. Instead, we ask them to think the way we think. There's no point in forcing the LLM to remember which well has the polymerase and which has the premix. It's much less error-prone to let it specify adding polymerase to the premix and resolve the well assignments deterministically. Similarly, expecting LLMs to do volume math seems misguided.

Third, there's no reason LLMs can't make Petri workflows. It may be ambitious to ask them to write the full JSON graph representation directly, but you can very easily give them a domain-specific language to generate the graph programmatically. And this way the LLM can benefit from all the same consistency and validation checks Petri already offers human users. The contention isn't really "code vs Petri". The contention is "abstractions vs no abstractions".

Values flow down, volumes flow up

One of the most interesting parts of Petri is the bidirectional dataflow. Petri automatically recalculates well volumes and well assignments to produce the requested amount of material, even when multiple sequential mix reactions need to be updated.

Petri rescales reactions as the amount of sample to produce goes up and down. When a sample has no downstream consumers of its volume, Petri removes it from the workflow completely.

This was tricky to implement for a few reasons. First, the logic for calculating what values a block provides is very similar to the logic for executing it. Ideally the same plan is used for both to avoid inconsistencies. Having a single control function that plans its own work, passes its plan to all of its children, waits for them to finish their calculations, then executes itself, and then triggers its children to execute is challenging to conceptualize.

Second, the volume constraints from every dependent are aggregated in the parent. And every block can request samples from multiple parents.

Third, the graph often changes. As upstream blocks change what they provide, downstream blocks have to add and remove pads and patch their affected links.

Adding and removing samples upstream changes what the "Breakout materials" block provides.

Fourth, Petri implements some profile-guided optimizations. This enables splitting input materials across wells when they exceed the well's volume. It also skips loading unnecessary plates and tips. Enabling the graph to run with skipped steps requires that the whole graph executes deterministically.

Finally, the same graph executing in your browser under simulation must execute the same way when executed by Petri's scheduler. And, if the network goes down or the server is terminated mid-run, it must restart and resume execution without repeating or forgetting any steps.

Critiques of Petri

There's a classic automation engineering joke about sales people claiming "there's no need for liquid classes! But for difficult liquids you can adjust the pipetting parameters."

Liquid classes are the most common critique of Petri's approach. They violate the belief that every pipetting motion is alike. There are other related flaws. Another example is that Petri doesn't predict ethanol evaporation.

I think this critique is stuck in the past: predicting liquid classes is obviously a task that an AI model can do. Yes, it requires collecting data. Yes, it requires effort. But there is so much redundant effort put into calculating liquid classes for every liquid that every automation engineer works with, and I'd hope that at some point that effort can be put towards a communal database to solve the problem.

Petri also doesn't support dynamic workflows: the graph has to be fully defined before starting. Indefinite length loops aren't possible. It would be easy to add if/else blocks that can choose a branch at runtime, but even then the workflow may require operators to load the worst-case amount of materials at the beginning. This feels good enough. Experiments should be reproducible, and workflows that have different behavior every time you run them create reproduction challenges. Dynamic control flow is often used to rescue failing steps. It's better to improve those sources of errors and make it so the process doesn't need interventions.

Another critique of Petri is that automation engineers often want to specify the pipette's pathing precisely. Since Petri doesn't let users control well assignments, you cannot control the pathing. I think this is similar to being upset about a compiler not using registers optimally. Automation engineers excel at maximizing performance and often view their job as the bioscience version of hand-writing optimized assembly. On the other hand, Petri aims to allow researchers to write the equivalent of C. Is it maximally efficient? No. Is it easy to write and allows researchers to solve real problems? Yes.

Also, as Petri improves, all workflows automatically benefit and the performance gap can be closed. Petri already automatically "vectorizes" sequential operations into a single multi-channel pipette operation (disabled on Opentrons due to accuracy issues).

So, is Petri useful?

Well, not yet. We've encountered one major challenge.

Petri makes it easy to set up workflows that will run for twenty hours straight. That means the error rate for every step has to be miniscule. We haven't yet dialed in our liquid handlers' properties for an acceptable level of performance. This is magnified by our decision to optimize it for prototyping: in an effort to reduce wasted materials we are asking for the machine to move very small volumes of materials. We need to dedicate time to figuring out a robust set of parameters for our liquid handlers that can be used as the basis for any workflow.

Aside from that problem, Petri correctly generates very complicated workflows that we have defined and executed. Luckily, because workflows are specified declaratively, increasing the robustness might just require changing the minimum pipette volume or the dead volume constants in Petri.

What's next for Petri

There's a lot more to do.

I want to add support for Hamilton Nimbus robots using our library Piglet and support new devices like plate readers. I also want to make a "Sequencer" block that waits for fastq files to be uploaded into a storage bucket, and cutadapt and Bowtie 2 blocks to process those sequencing results. Despite my aversion to well assignments, it should allow loading input materials on predefined plate maps. And it would be helpful to give Petri a way to estimate the time a workflow will take so it fits better into people's existing workflows.

But more importantly, I'm very curious to hear what people think about it. If you find Petri useful or have thoughts, please reach out!